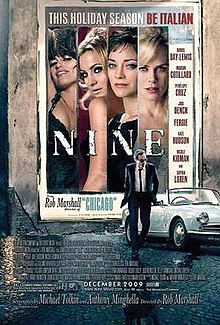

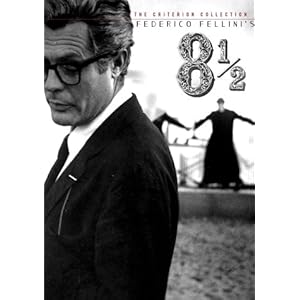

Last night, I watched Rob Marshall’s Nine (2009). The film, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and a star-studded collection of Hollywood actresses including Sophia Loren and Judi Dench, was a play on Fellini films, mainly Otto e Mezzo. The film follows the trials of the womanizing director Guido Contini, clueless as to how to make his next picture, as he faces pressure from the press, producers, and fans. Throughout the film, there are thematic and iconic references to Fellini films and intermittent song and dance sequences. Each character, with the exception of Louisa (Marion Cotillard) and Guido, gets a song, tailored to his or her personality or significance to Guido. For instance, Carla, Guido’s mistress (Penelope Cruz), sings dressed in lingerie about her lust for the director.

The film was somewhat difficult for me to judge. The venture and the outcome were both great achievements. However, this film faces twice as much pressure as almost any other original film because it is judged not only as a film in and of itself, but also in comparison to Fellini’s originals. Nine was based on a play, but certain cinematic techniques that can link Nine and Fellini’s work can be found only here. The comparison is more apt because the same medium is used.

At some points, Nine hits the notes perfectly. This was thanks to some wonderful performances;  Marion Cotillard was beautiful and Daniel Day-Lewis was wonderful in his Marcello Mastrioanni rendition. He slipped up on the accent sometimes – especially when pronouncing “Mamma” as “Mama” (nitpicky, I know, but important when his Mamma is a significant character and played by Sophia Loren) – but overall channeled the allure and absurdity of Fellini’s original well. The film also sometimes accomplished the melding of Fellini images and dance numbers. The most striking example of this is Saraghina’s “Be Italian,” during which a memorable scene from Otto e Mezzo is recreated and paired with the forceful and passionate song.

Marion Cotillard was beautiful and Daniel Day-Lewis was wonderful in his Marcello Mastrioanni rendition. He slipped up on the accent sometimes – especially when pronouncing “Mamma” as “Mama” (nitpicky, I know, but important when his Mamma is a significant character and played by Sophia Loren) – but overall channeled the allure and absurdity of Fellini’s original well. The film also sometimes accomplished the melding of Fellini images and dance numbers. The most striking example of this is Saraghina’s “Be Italian,” during which a memorable scene from Otto e Mezzo is recreated and paired with the forceful and passionate song.

There were also certain images and themes which connected Nine to it’s predecessors. For one, the clouds of cigarette smoke that swirled through each scene hearken unmistakably to Fellini films, as did the image of Daniel Day-Lewis in sunglasses with a cigarette dangling loosely from his lips. Marshall also utilized several themes that are common in Fellini films. Among them were infidelity and mockery of Catholicism, or religion in general. In La Dolce Vita, there is a rather amusing scene dedicated to the de-sanctification of religion in which pilgrims and press are made to run around according to the whims of children claiming to have seen the Virgin Mary. Similarly, in Nine, a priest explains that the church publicly denounces Guido’s movies, but secretly, they are all big fans. Another theme that this film has in common with Fellini’s and many other Italian films is the emphasis on and repeated depiction of children. These aspects of Nine were well-crafted homages to Fellini's films.

However, other aspects were not as cohesive. The dance sequence the fared worst was Stephanie’s (Kate Hudson) flashy Hollywood-Goes-Italian number. I understand this play on Fellini’s technique of inserting blond American stereotypes into the plot, but the addition is wrong for a couple of reasons. In La Dolce Vita, this figure, played by Anita Eckberg, has an effect on the main character even though in the long run she makes almost no impact on his life. In Nine, Stephanie really means nothing to Guido. Further, while most of the songs are from Guido’s perspective – that is, the songs depict Guido’s ideas of the women – Stephanie’s depicts her ideas of Guido. Perhaps the change in perspective was meant to signal some sort of development in Guido. However, therein lies another dissimilarity between this film and the originals.